Being ready, being prepared, being reconciled, being happy and at peace with the way you treat yourself and others – they’re all factors. Everyone has their own version of ‘living well’.

In these pandemic times, health, fitness and well-being are very much at the forefront our minds, and so for episode 20 of our podcast we spoke to the perfect guest to discuss the drive to live better – Elliott Reid. Elliott is the founder of the Revitalize Health and Fitness Centre in Gravesend, Kent and is an osteopath and personal trainer. He is on a quest to help people deal with pain and walk a better path.

Q: Elliott, you’re an osteopath and a personal trainer, let’s start by asking you a little bit about yourself, about your work and why you have the passion for what you’re doing?

A: My passion for health and fitness has always been there for as long as I can remember. I remember being ten years old and reading my first big psychology book, I read Awaken the Giant Within by Tony Robbins.

I was always interested in the potential of human nature; of humanity, how do we become the strongest version of ourselves, mentally, the smartest version of ourselves, so that’s always been there.

But then when I was sixteen I was boxing, and unfortunately I hurt my back a few days before I was supposed to fight, and I went to see an osteopath, and the osteopath was able to treat me and get me ready for a fight in three days’ time, so that planted the seed.

I then became interested in that profession, so when I applied to university, I included in my personal statement that I wanted to become an osteopath, which is a four year course, which I studied at the University College of Osteopathy.

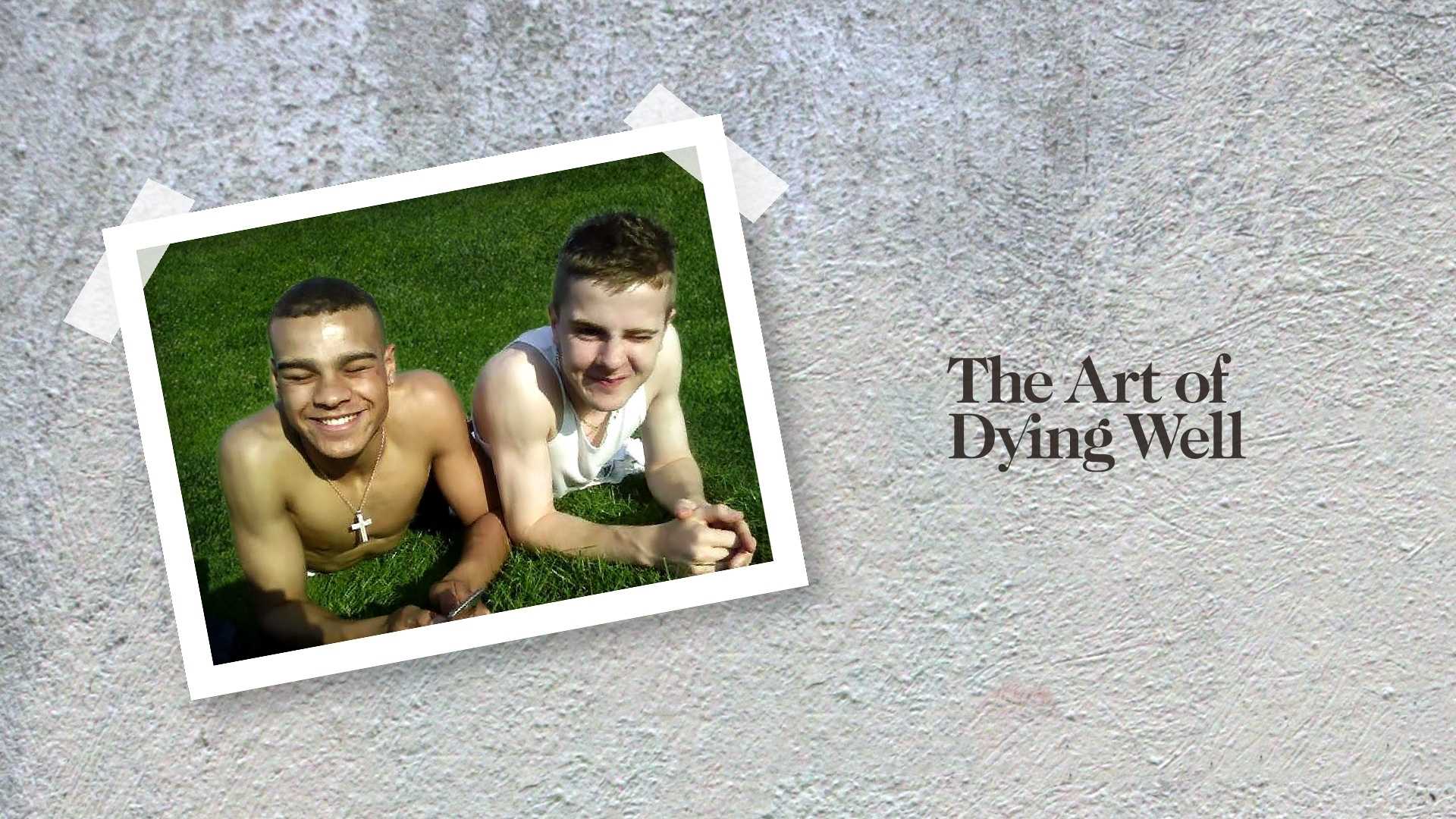

At the same time, just before university I had a very close friend die of Leukaemia. A year, two years went by, and I had another friend die of Melanoma; and they were both 17-18 at the time. Since then I’ve spoken to a few different professionals and therapists and I’ve come to the conclusion that I probably had a bit of a midlife crisis in my late teens.

What normally happens is that people in their fifties or their sixties, when they start to realise that time is running out; I really had that aged 17, and every single day, I suppose because of what happened when I was 17, I’m forced to view my life, or my day at least, as a sand timer I’m very, very aware that the time’s running out and I then have to view my time as currency and decide what I want to do best with that time.

My main inspiration, the main meaning that I get from life is by creating something to improve the existence of individuals while they’re blessed with their short amount of time on this planet. So that’s why the Revitalize clinic has taken quite a multidisciplinary approach people come in with depression, anxiety, pain; they might have high blood pressure, cholesterol, they can come in through one door and they have all the experts they need to help them to remove their barriers, to living a full, pleasant, satisfying existence whilst they’re on this planet.

Q: That’s amazing, and just to dispel a few myths, it’s always tricky with osteopathy, I always find it hard to define. Is it a sort of holistic approach, is it mental well-being as well as physical well-being?

A: Yes, it’s the same as trying to define modern medicine as what it was two hundred years ago; doctors were prescribing leeches, and electrotherapy, and trying to shock the brains of patients when they had schizophrenia all kinds of nasty things like that.

Osteopathy has moved on quite a lot in the past two hundred years since it was founded, but the fundamental difference is that you focus on the body’s capacity to heal, or you focus on the body’s capacity for self-regulation. Whereas if you compare that to a typical medical philosophy, it’s more about how you find the disease and how you eradicate it.

I suppose with osteopathy you’re forced to look at the body holistically because there are so many forms of protection that the body already has. So when we look at, for example, pain, the leading cause of pain, or two of the leading causes, or a few of them would be – poor sleep or depression, poor diet, poor exercise regime, poor belief systems. So if we flip that we then see that the body’s main defence against pain would be good sleep, good diet, good exercise regime, a good belief system, optimism.

So you’re forced to be holistic because you’re forced to try to use the body’s own mechanisms for healing, so that’s I suppose, the main difference between osteopathy and say more allopathic medicine. But the thing is we’ve got so much good evidence coming out of the industry; from osteopaths, chiropractors, psychotherapists, physiotherapists, psychiatrists, on what the body really needs, what the individual really needs, to get out of their own way and to live a pain free life. So you should find that most evidence-based practitioners, and I would call myself that, will practice very similarly, and as long as they’re evidence-based, you can’t really argue with the science which is pushing the industry in a really good direction in my opinion.

Q: I’d like to go back to that fascinating point you made actually, about what you described as a sort of late-teen, midlife crisis, it’s interesting because it sounds to me like it was almost a midlife awakening really. You lost two close friends, way too young to be dying. And that’s sort of shaped how you look at your own life and I guess your own profession. Is that a sort of mentality that you struggle to bring to people that come in and just want to be healed?

A: Absolutely, one hundred percent. If I try and apply my life lessons to my patients I can only take a patient as far as they want to be taken. My job is a guide. I can only guide the patient towards where they want to be, I can only utilise what the patient is willing to give.

If the patient is very aware that they’re going in the wrong direction when it comes to living a long, healthy, fulfilling life, and if they’ve got the proactive nature to do something about it, then it’s a very, very fulfilling path to walk with them.

A lot of patients come in with a bit of, I suppose, an assumption that despite the poor decisions they’ve been making for the last decade few decades that they’ve been making, that the osteopath is just going to go whack, whack, click, click, rub, rub, and they’re going to walk out pain free, which can be the case, but a lot of the time these patients keep coming back.

Unfortunately I think there are a lot of people who have been made passive, I suppose, by a western view of medicine which is that you go to the doctor when you’re sick, and the doctor takes the sickness away.

The issue with that is that was very, very applicable in say the 1930s, 1940s, when the NHS was founded, when the leading causes of death were workplace accidents, viral infections, bacterial infections. These are all things that really benefit from an allopathic perspective because yes, the doctor can put the disease under the microscope, or he can see the wound and bandage it up and your own healing mechanism will take care of it. But unfortunately the leading cause of disease now is lifestyle factors, the chronic bombardment of the body with poor diet, poor belief systems, poor mindset, poor exercise levels. You can’t really get to the bottom of these issues from an allopathic perspective, you have to get to the bottom of them from a therapeutic perspective, you have to guide that person, you can’t give them a pill for that ill.

Q: And in terms of the work at the clinic, have you treated people who have been terminally ill?

A: Yes, quite often, and sometimes it’s about managing their pain, as they’re about to finish their journey, and for some it’s about keeping them optimistic, and keeping them fit and comfortable, whilst they’re fighting – if it’s not terminal – that disease off. But I have had the pleasure of spending time, quite a bit of time, with patients who are terminally ill and the conversations are drastically different, the mood is drastically different.

Q: Yes, and you talked a little earlier about learning and being shaped by the death of close friends, do you find you learn even now, when you’re accompanying a terminally ill person or someone who is very sick?

A: You always learn what’s important. At the end of the day if we finish work at 5pm and its 4pm, we prioritise the most important tasks in that last hour, and when someone’s time is running out, you always learn what’s the most important.

When someone is passing and they’ve had someone who is passing that is a very, very personal experience for them, so it’s a very, very anecdotal experience. Carl Jung, one of the founding fathers of psychology said that research will show you the average of the individual but it won’t show you the depths of the individual. And a lot of the time, I think it is about more listening, and guiding that individual to where they want to be.

A lot of the time the experience of an individual is shaped by the relationships they have; by their relationship with their history and what they have been through before. Personally, it shapes me because I really learn how varied human beings are, and yes, we do have core components, we prioritise love, company, creativity, development, legacy, all these things are quite common to a lot of individuals, but it still rests on the individuality of the individual that I’m seeing at that point in time.

Q: I really like that analogy of the four o’clock time, when things close at five. It makes me think a bit about those who are dying. I’ve read testimonies and spoken to people that when they have been given a terminal diagnosis, and they know that their time is short and that they’re going to die, they say I wish I’d been this focused, this reconciled a little bit earlier when I was still healthy. Do you hear that psychology at all?

A: Yes, you’re talking about the psychology of regret right, which when it comes to dying well – I think using your time whilst you’re alive to imagine what you would regret – and work to make sure that you do not regret anything when your time is coming to pass.

Q: It’s a little be carpe diem isn’t it? Seize the day, don’t wait.

A: Absolutely, and through myself going to therapy and speaking to our therapists here, and from speaking to other people; there are so many individuals who are constantly working through their defence mechanisms. So this might be anger, it might be to fit in, it might be social conformity, it could be to appear well to their peers; all these defence mechanisms which are there to satisfy the psyche, to make sure that the psyche is protected, to make sure that individual is – I suppose – protected throughout their existence, their normal archetypal experience.

The whole time that your defence mechanisms are up it’s very difficult to see yourself, it’s very difficult to feel the relationship with yourself. And the one thing that I do see, one hundred percent, is that when people are terminally ill their defence mechanism is gone. They are no longer trying to protect themselves because there’s no need at that point in time. They know that their time is imminently going to be up and it’s at that time, that they might actually start, for the first time, to realise who they are. That’s beautiful but it’s a real shame at the same time. Why do individuals have to wait until they realise that time is really up to seize the day, to realise who they are.

I very, very much advise anyone who wants to develop a deeper relationship with themselves to go to a therapist, with the goal of that therapist coaching them to understand who they are, and it’s very, very likely, and I have to be honest with you, the same thing is available through religion. I think religion is a great way to understand who you are and what’s important to you, through meditation, through self-reflection. I very much advise that people go through that process whilst they have the time.

Q: And this might seem a little unfair, and putting you on the spot, but if you had to come out with a sentence or two instantly off the top of your head what would you say dying well looks like? What is dying well in your opinion?

A: I suppose dying well for me is contextualised by my life, right, I think that if I can be on my deathbed and say that there is not really one point in time where I would have done anything different, that for me is the perfect ending to my book, or to my life, having peace to just retreat into myself on my deathbed, and knowing that I’ve done a good job, I think that’s what dying well means to me.

Q: And conversely, what would you say is living well?

A: Living well for me is leveraging every speck of time that I spend on this planet to help as many people as possible. That’s what I obsess about; how can I help more people, how can I create infrastructure, how can I improve my skillset, how can I improve others skillsets, my team’s skillset, improve our reach to help as many people as possible, that’s the way that I view life.

I think that’s the way I view life in terms of what I most enjoy doing proactively, but then as well as that there’s building a healthy relationship with my family, making sure that I am living well in my family’s eyes. Making sure that I’m living well with my fiancée, my future wife, in my children’s eyes. The ancient Egyptians used to believe that the soul dies twice, once physically, and once secondly when people stop saying your name through libation, and I have to say that I would agree with that, the more good work you’ve done, the more people are speaking of you after you’ve gone and retelling your story, I think that’s a very good way of measuring how valuable your life was.

Q: And those young men that died too soon, those friends of yours, do you still – in light of what you’ve just said about the ancient Egyptian philosophy – do you still think about them a lot, do you recall them?

A: Every day. I’ve got a picture of my friend Ben in my clinic room, so every time I walk in I see him, and I definitely know what I remember about him; his attitude, his drive, his beauty. There were aspects of his character that were beautiful; whether that was his sense of humour, camaraderie, all these nice things so yes, I remember him and speak about him often.

And Daniel is another friend who passed, I remember him and speak of him often, he was very, very charismatic, a very creative individual, very, very headstrong, and I think that’s you know, now that I’m thinking about it, I’m reflecting on myself and my own interpretation.

I always remember that when people pass I remember when they stood up and they said something. I don’t remember when they retreated. I think that’s also a good thing for me to acknowledge and to live by, that every single time that we speak up, and every single time that we stand our ground on something that we believe in, or believe is important to us, we’re shaping the world for a better place.

Every time that we take a step back and we don’t say anything; because we want to keep face or we don’t want to hurt someone’s feelings, even though what we have to say brings value to the table; people don’t remember that, people remember when we as individuals stand up and say something, and do something for the better.

Q: Spot on. That’s really inspiring Elliott. Let’s just turn our attention to Covid-19, because obviously you’re a business and you’ve got a wonderful philosophy behind your business to help people and to continue improving, but it must’ve been hard for you during lockdown, and possibly even post-lockdown, how did you cope during those months?

A: Well, I had to gain perspective, right. We lost two to three months of revenue and had to pay two to three months of overheads, but I lost people who I knew due to the virus, I would’ve paid that a hundred times over to keep them alive. So, I’ve got my life, I’m healthy, I’m fit, my family are healthy and fit. I’m grateful. It was difficult but when you’re dealing with death it’s a no brainer. I happily closed my doors for two, three months to slow the spread, and now we’ve opened back up, obviously we’re making sure we’re fully equipped with PPE, putting all the regulations and policies in order to make sure that our patients are protected. So for me, I was happy to close my doors, it was a duty I happily partook in.

Q: And in terms of where we are now – post-lockdown – people still have that anxiety don’t they? They’re still concerned about a second spike and about whether that means we’ll have to isolate and be separate from one another. Are you finding that people have a different mentality these days, are they more health conscious, do they want to look after themselves better because of the pandemic and the shadow that’s cast?

A: It’s seems that people are definitely more health conscious. What lockdown really taught us is what is truly valuable and what people really missed, and social interaction was one. People were going out for more walks, running, getting out into the countryside, really focusing on what they value.

There’s more people I speak to, professionals, who are refusing to go back into the office full-time because they realise how valuable their spare time is. So I would say there’s a definite shift. I think there are some people who are very cautious, understandably so, but the numbers, at least here in Kent, the numbers are very promising, I think it’s about one in about 7,000 people has coronavirus in Kent at the moment, and the numbers are dropping.

Q: And that’s a big county isn’t it, so perhaps there’s grounds for cautious optimism.

A: Yes, cautious optimism is the way forward I think, absolutely. So make sure that you’re being safe but living your life.

Q: Elliott, it’s been absolutely fascinating, but one final question, what would your encouragement to those that are thinking I do need to make a change, I’d like to live my life better, I’d like to live well.

A: It’s very, very specific to the individual, because some people value that bottle of wine every evening, and a takeaway every so often rather than eating their fruits and vegetables, and living a long life.

I think the best thing that I could hope for people is that they get out of their own way. I think the best way to do that is to be able to see your mind and to realise that you are not your anger, you are not your anxiety, you are not your greed or your gluttony, you are none of these things.

You are the captain of your ship. You have these crew members on your ship, and these crew members might be anger, jealousy, greed, which are useful at certain times right, you can use those in the right situations, at the right time, but to realise that you are the captain of your ship, at least then, through the pursuit of consciousness, and through the pursuit of understanding yourself, and knowing yourself, you can then coordinate your life to reach your true potential, and you’re not purely reacting to social norms or reacting to these inner drivers that we all have.

So I think the biggest hope I would have for an individual is that they pursue trying to realise who they are, and once they realise who they are, and once they can captain their ship, that they captain their ship for the betterment of themselves and for hum.

*Content courtesy of artofdyingwell.org